Stephen Kenny's appointment brings echoes of the last time Ireland appointed a home-based coach to the senior international job, with the remit of reinventing a stale Irish side with an injection of young, promising footballers.

I have a personal motivation for undertaking a retrospective of Brian Kerr’s Ireland tenure. I was

fourteen years old when Ireland won the U16 and U18 European Championships, eighteen

when Kerr got the senior job, and twenty-one when he was sacked. I spent my most

formative years, the years that shaped my personality as an adult, truly

believing that a great era of Irish footballing dominance was on the horizon –

a generation of success to eclipse anything achieved under Jack Charlton. As a

teenager, I played out those fantasies on Pro Evolution Soccer,

where my genetically-modified Irish teams swept to World and European glory; Stephen

McPhail threading sumptuous passes for Robbie Keane; Damien Duff and Richie

Partridge cutting through defences with Maradona-like evasiveness; Richard

Sadlier dominating in the air like an Irish Oliver Bierhoff. That was, I hoped,

the true destiny of the Irish team in the New Millennium, and Kerr would be the

man to deliver – as soon as Mick McCarthy did the decent thing and finally

stepped aside.

Kerr had been around a

while – a spell as assistant to Liam Tuohy in the youth setup in the mid-eighties

came to an end when Tuohy clashed with Jack Charlton, and Kerr remained a

critic of Big Jack’s style of play and abrasive relationship with native coaches.

He had a fruitful period with St. Patrick’s Athletic in the late eighties and nineties before

taking the Irish youth job, winning two titles. He was known for being that

rarity in the mostly amateur Irish domestic game – an ambitious, knowledgeable

professional. A semi-final appearance for Ireland in the 1997 World Youth Cup

was unprecedented, made even more impressive by the fact that it wasn’t a

star-studded Irish squad – Damien Duff was the only player who would go on to make

a competitive senior appearance. It was a team of future journeymen and League

of Ireland stalwarts that eliminated Spain, and competed so manfully against an

Argentina side boasting Samuel, Riquelme, Placente, Scaloni, Cambiasso and

Aimar. It spoke volumes about Kerr’s ability to take a rag-tag group and get

them playing confident, constructive, winning football.

Later, he would also prove capable

of taking strong, highly-rated squads, and delivering on expectation. The 1998

European Youth Champions boasted not only Robbie Keane and Richard Dunne, but

future caps Barry and Alan Quinn, Gary Doherty, and Stephen McPhail, as well as

the highly-rated Jason Gavin and Richie Partridge, who would gain senior

experience with Middlesbrough and Liverpool. From the U16 cohort, John O’Shea, Liam

Miller, Andy Reid, Joe Murphy, John Thompson, Jim Goodwin and Thomas Butler

would all win caps, while Colin Healy and Richie Sadlier (in the group that

competed in the 1999 World Youth Cup) were also future internationals. In 2002,

the Irish U-18 squad came third in the European Championships and qualified for

the 2003 World Youth Cup – from that squad, Stephen Elliott, Stephen Kelly,

Glenn Whelan, Kevin Doyle and Keith Fahey would eventually be capped.

It was a seemingly

phenomenal stream of Irish talent, brought through by a man who could seemingly

harness their abilities, create an ambitious, positive environment, and

encourage them to compete to the fullest of their potential – to beat the future

stars of Spain, England, Croatia, Italy, Portugal, and Germany.

While Kerr was making

a name for himself, McCarthy’s senior side were struggling. The autumn of 1999

was an exasperating time – a squad which had shown itself capable of beating

Croatia and Yugoslavia was reduced to a rabble by some bizarre decisions and monstrously

negative football. Washed-up veterans like Cascarino and McLoughlin were stinking

up the side, and when Roy Keane was injured, the midfield was patrolled by

unimpressive, one-dimensional, English-born journeymen like Carsley and Holland.

The immense talent of Damien Duff was reduced to hugging the touchline, hoofing

crosses into the box, with Gary Kelly out of position on the other side. Turkey

passing Ireland off the pitch in Lansdowne was a low point, when placed in such

stark contrast to the youth teams’ excellence; it seemed farcical that Stephen

McPhail was ignored despite playing well for a top-three Premiership team and

UEFA Cup semi-finalist, while the incumbents – Kinsella, Carsley, McLoughlin

and Holland – were all plying their trades in the English second tier.

McCarthy’s fortunes

changed dramatically when he abandoned the negative tactics and tried a more progressive

approach (who knew?) but even throughout the 2002 World Cup campaign, and the

coming of age of Dunne, Keane and Duff, there was a sense that this was just

the beginning. When Kerr eventually took the job (a prospect that seemed more

likely in the fallout of Saipan), it seemed certain that the older, willing but

limited senior pros would be cast aside to allow the more dynamic, pacey,

technical young players to make their mark. By 2002, O’Shea was playing first-team

football at Man United; Partridge and Barrett had debuted for Liverpool and Arsenal;

Healy had made a European debut for Celtic; Sadlier was scoring goals in the First

Division; Andy Reid had broken into Nottingham Forest’s team at eighteen; McPhail,

the Quinns, Doherty and Gavin had built up a good body of Premiership

experience and not looked out of place. Barrett and Healy demonstrated their

potential by scoring in a post-World Cup friendly against Finland. There was

also an outstanding young Shelbourne playmaker called Wes Hoolahan who looked

destined for a career at a higher level, and was named in a senior squad

towards the end of the year. While Saipan had divided the country, and the Far

East adventure had been compromised by thoughts of what could have been, the future

still looked bright.

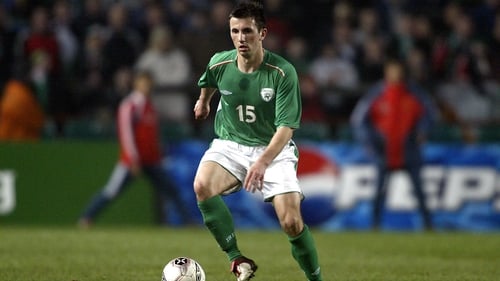

|

| Graham Barrett, with Kilbane and Healy, celebrates his first goal for Ireland |

Kerr’s appointment

looked like a rare sensible decision by the FAI. Names like Bryan Robson and

Philippe Troussier hadn’t inspired confidence, and David O’Leary had unfinished

business with Leeds. Shorn of Roy Keane, Ireland had looked tired and bereft of

ideas in their home defeat to Switzerland. Without

their disgraced former captain to cajole and elevate those around him, the

likes of Breen, McAteer, Holland, Kinsella and Kilbane looked incapable of

adding anything beyond blundering, misdirected graft. It was 1999 all over again,

and the departure of McCarthy came as something of a relief. Ireland needed

a coach with imagination and ambition; a belief in youth and a progressive style

of football; someone who would encourage the best from his players. Kerr seemed

like a perfect fit.

It was curious, then,

to see the same old, same old for the game away to Georgia. A midfield of

Carsley (on the right wing, bizarrely), Holland, Kinsella and Kilbane laboured

to a 2-1 win in Tbilisi and an uninspiring four points against Albania, the

home game won with an own goal in the last minute after a dreadful display. The

1-1 draw at home to Russia was equally dismal, and the campaign petered out with

an insipid defeat in Switzerland. Kerr hadn’t made any changes, aside

from bringing John O’Shea into the starting XI. It was understandable (in a way)

to give players who had done so well in 2002 one more campaign to show their

worth before genuinely reinventing things, but it should have been clear from the outset that some

players were spent forces, or just technically not up to it. Andy Reid and Liam

Miller made their debuts in the 2003/4 friendlies, while Barrett and Alan Quinn

shined in an excellent 1-0 win in Amsterdam in June 2004. It seemed like this

was the template for Kerr to build his team for the 2006 qualifiers. With Roy

Keane committed to a return, it would have made sense to populate the other

midfield places with younger, faster and technically adroit players.

One of the big

quandaries was the almost-inexplicably bulletproof status of Kevin Kilbane. A

weak link in the 2002 side, his hard running, aerial ability and defensive work

was compromised by an infuriating propensity for wasting possession through poorly-controlled

balls and wayward distribution. A James McClean prototype, one might say. Kerr

kept faith with him, often relegating Duff to positions on the right and up

front where he was less effective. Instead of dropping him, Kerr decided to accommodate

him in central midfield, the logic being that his athleticism would prove an

effective foil for Roy Keane – still a force, but a significantly less mobile

player than in times past. Sometimes, it worked; other times, Kilbane’s

technical limitations and headless ball-chasing were exposed even more ruthlessly

than on the wing. In retrospect, Steven Reid would have been a much better central

midfield partner – even the more diminutive Miller, Andy Reid or McPhail would

have benefited from the freedom of playing alongside one of the world’s best defensive

midfielders. It’s a great pity that Colin Healy was so badly affected by a

succession of serious injuries.

The experiment seemed

to be working, as Ireland topped their group in the autumn of 2004, drawing

away to Switzerland and France. The latter was a particularly eye-catching

performance, as Ireland passed with confidence and purpose, putting themselves

in a great position with back-to-back games with Israel to come. That night in

Tel-Aviv proved to be a turning point for Kerr. It was a repeat of Mick

McCarthy’s Skopje nightmare in 1999, when an early lead turned the game into a

battle of containment, follied by a late equaliser. Kerr’s negative tactics

played into Israel’s hands, as Ireland sat back and invited pressure, which was

inevitably rewarded in front of a partisan crowd. Bringing on Matt Holland for

one of the strikers – as McCarthy had done six years previously – completely

ceded territory and possession, and Kerr was punished. With Ireland struggling

to keep possession and establish a link with the front players, surely Andy

Reid – in the form of his career – would have made more sense as an extra

midfielder; but he remained on the bench. Hindsight is a wonderful thing, of

course, but the sense of déjà vu was overwhelming. Kerr did exactly what

McCarthy had done in his worst moment.

The return game was even

more unforgiveable. With Roy Keane absent, Holland and Kilbane manned the

centre of midfield – an alarming prospect. However, thanks to the set-piece

brilliance of Ian Harte, the vision of Reid, the dribbling of Duff, and the

cheeky finishing of Robbie Keane, Ireland found themselves 2-0 up. Fatefully,

the Spurs striker hobbled off injured, and Kerr was forced into a decision –

straight swap, or total reshuffle. He decided to bring on Graham Kavanagh – another

in our long line of limited thirty-something journeyman midfielders – and push

Duff up front, allowing Kilbane to go to his natural role, wasting possession

on the wing. Immediately, we had two ageing, immobile players in the

engine-room and virtually no attacking threat on the left, with Duff moved from

where he had been causing havoc, into an isolated role alongside a static Clinton

Morrison, who was having one of his more ‘laid-back’ games for Ireland. Israel grew

into the game, and while their goals were somewhat fortuitous, it was an almost-inevitable consequence of Kerr’s negative changes. While the shithousing antics of

Dudu Awat provided the game with an appropriate villain, the manager’s role in

two dropped points could not be ignored. A few days later, Stephen Elliott made

his first competitive start for Ireland against the Faroes, and showed why he

would have been a much better replacement for Keane, with a lively, pacey

display.

The game against

France yielded a better display, with Roy Keane giving his final masterclass

for Ireland, but his midfield partner had a torrid day; Kilbane constantly ran

into blind alleys, looking every bit a man out of position. Henry’s wondergoal

gave France the win, and a first home competitive defeat under Kerr. It would

be an uphill struggle to achieve a playoff place from there – Ireland would

have to beat Cyprus and Switzerland.

The game in Nicosia foreshadowed

the 2006 Staunton debacle, as Ireland were outclassed for much of the game.

Only a magnificent penalty save from Given and an opportunistic finish from

Elliott gave Ireland a 1-0 win, but there was little to suggest Ireland would

have enough to overcome the Swiss. So it proved on a miserable Wednesday night

at HQ, and Kerr didn’t help his cause by naming John O’Shea and Matt Holland in

midfield, with Kilbane seconded to the left. Shorn of Duff and Roy Keane,

perhaps Ireland just didn’t have the personnel to get a win, but more could

have been made of the available squad. Steven Reid was sitting on the bench,

surely wondering what he needed to do to get an opportunity. Liam Miller may

not have excelled at Man United, but he surely would have fared better than the

out-of-position O’Shea, and provided some form of passing ability and goal

threat. Aidan McGeady was in the form of his life, but was still ignored when

the Irish midfield needed something – anything – besides the same old huffing

and puffing. There is a rough, cruel irony that the last act of Brian Kerr’s

Irish career – the man who was feted as a progressive believer in youth and the

Beautiful Game – was a long ball hoofed by Shay Given, hoping to find the head

of Gary Doherty in a crowded Swiss penalty box, as the same tired faces from McCarthy's final game in charge - Kilbane and Holland - lumbered

around in midfield to the same minimal effect they had offered in the three intervening years.

Kerr was predictably

dismissed a few days later, and it was jarring to hear him, on an RTE documentary

shown that Christmas, claim that ‘maybe we just didn’t have the players.’ Kerr

had at his disposal a prime Given, Carr, Finnan, Harte, Dunne, O’Shea, Duff, Robbie

Keane, Andy Reid, and Steven Reid. He had a 34-year-old Roy Keane, who was still a

force at international level. He had young players who did well in friendlies, but were jettisoned when the serious business began, like Miller, Alan Quinn, Barrett,

Elliott and McGeady. Perhaps if Kerr had showed the kind of imagination and bravery he'd demonstrated in his underage years, an opportunity could have been found for someone

like Wes Hoolahan, then playing in the SPL. Kevin Doyle was scoring goals in

Europe for Cork, and later the top end of the Championship for Reading, and Daryl

Murphy was making waves at Sunderland and scoring freely for the U21s, while Kerr was persisting with Gary Doherty

– a centre-back who hadn’t played regularly up front at club level since the

age of 18, at Luton Town. Given that weaker Ireland squads have qualified for tournaments

in recent history, it’s clear that it was Kerr’s decision making, conservatism,

and lack of trust in his young players that sealed his fate.

Poor management is one

factor; there is one other at play.

Kerr and his assistant, Chris Hughton, demanded a high level of professionalism from their players, a fact welcomed by

Roy Keane, who was sick of the drinking sessions and haphazard preparation

under both Charlton and McCarthy. However, the video and tactics sessions and all-round

tight ship under Kerr did not meet with the approval of the players, many of

whom saw their international breaks as a welcome change of pace from the day-to-day

grind in an increasingly tactical and foreign-influenced English game. That

reflects more on the players than Kerr, who was ahead of his time in this

regard. Also, there have been murmurings about players, having attained wealth

and status in their careers since their youth days, not taking Kerr seriously enough.

It was instructive to hear Gary Breen – dropped by Kerr in favour of Andy O’Brien

and Richard Dunne – talking recently about how players may not respond as respectfully

to Stephen Kenny, as someone who is virtually unknown in England, as opposed to

the likes of Trapattoni or O’Neill. If that was the attitude towards Kerr, then

the fault lies with the ‘Billy Big Bollocks’ attitude of the players. Danish

and Swedish players – even the big egos of Ibrahimovic and Eriksen – have

always responded positively to their national coaches, even those who had never

coached outside Scandinavia.

Furthermore, we have

the issue of Irish players failing to make the best of their potential. Keith

Foy was a promising left-back at Nottingham Forest, one of the key players in

Ireland’s U16 European Champions, scoring a wonderful free-kick in the final

against Italy. In an interesting interview in 2018, he admitted that the lures

of going out on the town, with the status of a young professional footballer in

a medium-sized English city and the temptations it brought, were too much to

resist, and he quickly went from being a regular starter for Forest to a

part-timer at Monaghan United. Too many Irish players succumbed to the lure of

booze and birds; too few showed the professionalism required to extract the

maximum from their natural talent. Why didn’t the likes of McPhail, Hoolahan

and Andy Reid hit the gym a bit harder, when it was clear a lack of strength

and athleticism was holding them back? Why did so many gifted players from those

youth teams succumb to career-hampering injuries? This may be speculative, but could it have been substandard

nutrition and fitness, and haphazard rehabbing, making them more susceptible to

strains and tears, or inhibiting their recoveries?

British and Irish youth culture

in the mid-2000s was one of binges and excess, and many a promising football

career fell victim to it; in later years, Darron Gibson and Anthony Stokes

would come to personify this wastefulness. Maybe certain players should have tried

harder to give Kerr a more compelling case for inclusion. For all I’ve lamented

over the years about Kevin Kilbane’s technical deficiencies, at least he made

the absolute best of his talent and showed genuine determination and

professionalism throughout his career, like Glenn Whelan after him.

The Brian Kerr era

will always go down as an opportunity wasted. Given, Dunne, Duff and Keane should not

have waited ten years to play in another international tournament, by which

time they were long past their prime. Roy Keane should have had his chance of

redemption in a green shirt. The stars of the underage teams between 1998 and

2002, along with their manager, should have been able to produce on the senior

stage. But the perennial Irish bugbears of fear-based conservatism and poor

decision-making in our management; added to a lack of confidence, determination and self-discipline

at the level of the individual, ensured that our dreams would not be realised.